Cowley County, Kansas, has over the years built many stone arch bridges. Waterway was a problem encountered when building stone bridges, and over time the county began to design unique bridges to try to reach an optimum balance between waterway and expense.

How it Began

Cowley County, Kansas, at first was not overly worried about waterway in regards to bridges. This is evidence by the fact that, according to Walter Sharp, renowned Cowley stone bridge builder, when the county built its first major stone bridge over Timber Creek in 1902, lawsuit was threatened against the county for obstructing the stream in that fashion! This original bridge consisted of one span of 36 feet; it was apparently patterned after several bridges in Butler County. Butler County pioneered in stone bridge construction, and Cowley County was copying the county’s designs, first touring Butler to see Butler’s stone bridges. It’s hard to say what specific bridges the Cowley County commissioners visited in Butler, but the 36-foot Wilson Bridge near Augusta, which had been specifically visited by Greenwood County Commissioners when they were looking to build stone bridges, is a likely candidate. Also, the Ellis Bridge would have been under construction around the time and is another possible candidate; both these bridges were built by Walter Sharp. Walter Sharp always stated that the courthouse janitor was responsible for involving Cowley County in stone bridges. The janitor suggested to the county commissioners that they could build affordable, permanent stone bridges, and he knew of somebody named Sharp who was in the business of doing just that in Butler County. The Cowley commissioners investigated; the rest, as they say, is history.

The Waterway Problem

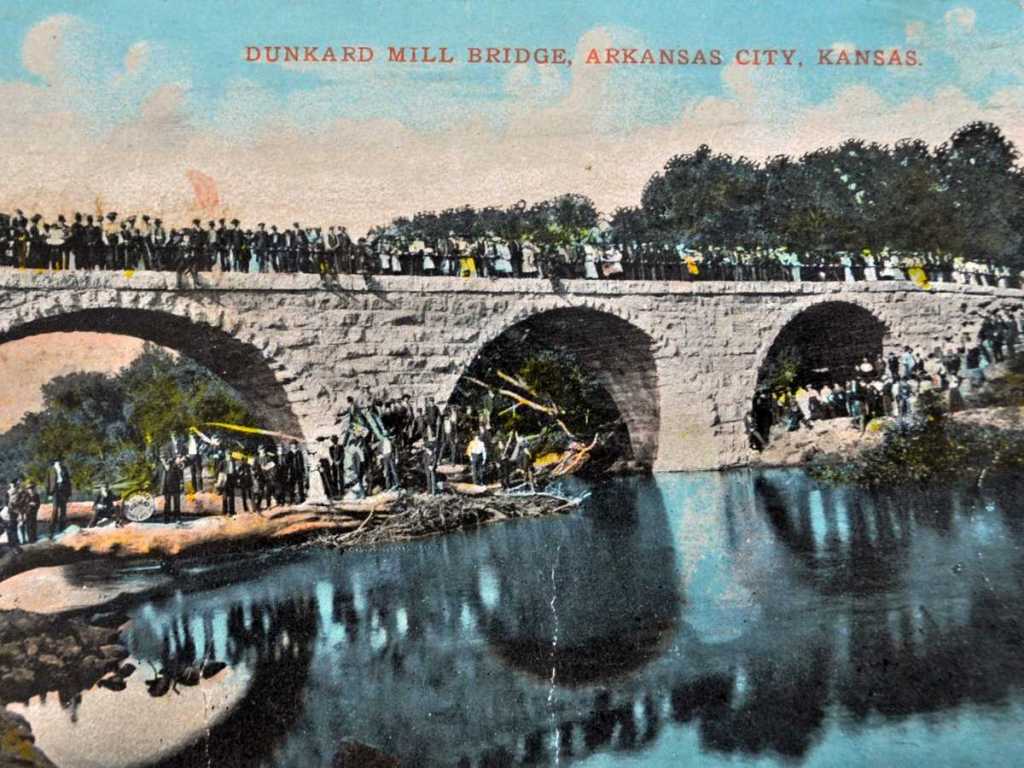

The major Dunkard Mill Bridge over the Walnut River showcased the problem with some of Cowley’s early stone bridge designs. Shortly after completion, a flood came and the bridge backed up the waters, resulting in an inundation of the surrounding countryside, which was in a degree checked when the water finally burst its way through one of the bridge’s approaches. To fix this problem, Cowley commissioners decided to add another arch to the bridge where the washout was, both to complete the bridge and to improve waterway.

Though Cowley was, according to the old newspapers, content to design stone bridges that were expected to be submerged during major floods, one of the major problems with Cowley’s early bridge designs with multiple spans was the pier(s). The above-mentioned Dunkard Mill Bridge, for instance, had a tendency to gather debris on the piers. To remedy this, cutwaters were later added.

One of the problems Cowley County still had with piers was the fact that the arches began at low-water level. This meant that a large section of wall above the arches was left in or near the middle of the stream, greatly reducing waterway. This was a problem with most double-arch bridges in Kansas, and always was a weak point in the bridge, for this middle section of wall was prone to washing out.

However, Cowley County was soon to innovate in stone bridge design, and to receive help in this matter from an unexpected source.