Cowley County not only designed innovative stone bridges, but very early on the county became known for its record-size stone arch bridges.

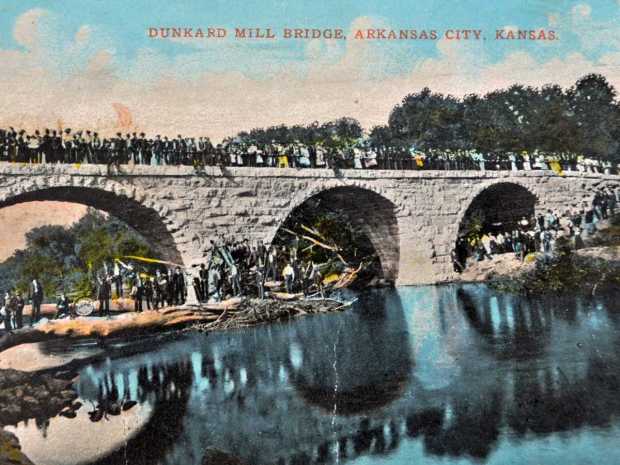

The Biggest Bridge in the State

The Dunkard Mill Bridge was the biggest stone arch bridge in the state when it was built. Originally, it had three 50′ spans; surpassing even Greenwood County’s quadruple 36′ arch Gleason Ford Bridge for waterway. Then, when the 150′ waterway of the Dunkard Mill Bridge proved inadequate, a fourth 40′ arch was tacked on to make up for the fact. The bridge in its final form was huge: four arches, 190′ aggregate waterway, and a rise of 23′.

The Dunkard Mill Bridge was destroyed in an unprecedented flood in the 1940s, though even today substantial ruins are readily visible if you know what you are looking at. The only other stone bridge in Cowley that ever came close to the Dunkard Mill Bridge in size was the Esch’s Spur Bridge, which has three 50′ arches.

Record Spans: The Goodnight Bridge

Cowley set some span records for the individual arches in some of its single-arch bridges. In 1904, Walter Sharp built the Goodnight Bridge over Grouse Creek near Dexter. This single-arch bridge, with a span of 64′ and a rise of 19′ was quickly was heralded as the largest single-span stone bridge in the state after completion, and Dexter was rather proud of this $2,000 bridge. Bypassed when the blacktop Grouse Creek Road running out of the southwest side of Dexter was built, only a shattered remnant of an approach remains of the Goodnight Bridge.

Incidentally, other traces of the old line of Grouse Creek Road can be seen if you know where to look; concrete arch culverts or their ruins can be seen in places, and a remarkable 30′ Walter Sharp stone arch bridge that formerly carried the old road still spans Horse Creek, though on private property.

The Goodnight Bridge briefly lost its record status in 1905. Outside of Augusta, in Butler County, Kansas, a 66′-span stone arch bridge was built over the Whitewater River on the west edge of town. This big bridge was not built by Butler County, but actually by Augusta Township. It was not a success; it only stood a few months before collapsing, apparently due to scour. The foundations, though deep, were not on rock, but instead on a soil described by an Augusta newspaper as being like quicksand. After the failure of this Whitewater River Bridge, the longest span in the state was once again the Goodnight Bridge, though only for a short time longer.

Record Spans: The McCaw Bridge

In 1906, a Cambridge mason and quarryman named Abe Finney undertook the building of a bridge over Grouse Creek north of Cambridge known as the McCaw Bridge. This bridge was to have one 70′ span, surpassing the Goodnight Bridge in size.

The construction of the McCaw Bridge went smoothly from all accounts, and by 1907 it was complete. Immediately the bridge received massive newspaper attention, for it was unequivocally the longest single-span stone arch bridge in all of Kansas. Abe Finney had done an excellent job, and this massive bridge cost only $1,845, according to the February 13, 1909, edition of the Winfield Daily Courier. The bridge consisted of a relatively low-rise segmental arch, one which had a span of 70′ and a rise of 18′. The arch ring itself was 2.5′ thick, surprisingly thin, considering the span, giving the McCaw Bridge a graceful appearance.

Not too long after its acceptance, the McCaw Bridge received another round of attention. There appeared to be a hole in one of the bridge abutments. This verified, the county commissioners had Walter Sharp repair the damage. Upon building a cofferdam and pumping out the water, Walter Sharp made the startling discovery that the bridge apparently had been dynamited. An enormous hole had been blasted into the bridge, and many cubic feet of masonry blown away, and the wonder was the bridge hadn’t collapsed. Walter Sharp repaired the damage by filling in the hole with concrete. There was speculation on whether the damage was deliberate sabotage, or perhaps somebody merely had an accident while trying to fish with dynamite. No definite conclusions were reached as far as we could find. The McCaw Bridge, later dubbed the Fox Bridge, served the public until its complete collapse in 2016. Local rumors say that the collapse was due to the raging waters washing out the mortar, etc. between the arch stones. However, bridge inspection records show that the foundations had been steadily deteriorating beginning but a few years before the collapse. Cowley County simply described the collapse as being caused by the brute force of the water.

The McCaw Bridge apparently had been modified at one point, for some of the stonework on the west end did not match the rest of the bridge. Perhaps it was added to eliminate any hump in the road; when the bridge was originally completed it was said that the McCaw Bridge ended neatly in the river bluff on one side, while the other side had a steep approach. However, having driven on the McCaw Bridge before its collapse in 2016, we can verify that the road wasn’t particularity steep, suggesting that it had indeed been modified at some point.

Record Spans: The H. Branson Bridge

The H. Branson Bridge as far as can be determined always had the longest stone bridge span in the state for as long as it survived. This bridge is usually known as simply “Branson Bridge”; however there was another stone bridge on Grouse Creek nearby sometimes called the “L. Branson Bridge,” hence why the H. was added to the Branson of the big 75′ Grouse Creek bridge.

The story behind the H. Branson Bridge is somewhat strange; it all began in a highly unusual bridge-letting that proved to be something of a free-for-all. Everybody was invited to bring plans and bid on them for any kind of bridge at a variety of locations, including the H. Branson Ford on Grouse Creek. It took the commissioners a while to sort through all the plans presented, of which there were many. Finally, Walter Sharp’s plans for a double 50′-arch stone bridge were accepted. How the bridge went from being a double 50′ to a single 75′ arch is something of a mystery. Either way, what Walter Sharp actually built was an enormous bridge: one span of 75′ with a rise of 21′. This was a very well-built bridge from all accounts, and cost $3,200.

The H. Branson Bridge collapsed some time in the early 2000s. It had already been closed to the public for some time, and a change in the shape of the arch clearly heralded major structural problems. The cause of the collapse is unknown; everything from scour to sabotage has apparently been suggested. The distinct 3-hinge failure mechanism does not preclude any of the above possibilities, but still suggests major overloading of the bridge. Perhaps something too heavy drove over it at some point; or it could be that loss of mortar weakened the arch. Since there was little weight over the arch (as is true for most of Walter Sharp’s bridges) and the span was so long, such a bridge would be rather vulnerable to overloading, even by its own self-weight if the relatively thin arch ever was weakened in any way.

Conclusion

Cowley County, Kansas, built many daring stone arch bridges. It is little wonder that the county became famous for its big stone bridges, of which, sadly, relatively few remain. Still, the remaining bridges are worth a visit and are an important part of the county’s heritage.