Walter Sharp wrote a very interesting series of articles entitled “A Story About Bridges,” in which he describes some of the story behind Cowley County’s stone arch bridges. In this article, Sharp primarily focuses on Cowley County Commissioner William Huston, but also leads up to the final chapter of his story in which he describes the events that prompted Cowley to stop building stone arch bridges. He also in an indirect way describes how stone bridges were built in Cowley.

Chapter 2

“The 10 years that have elapsed since the events of the preceding chapter have brought about many changes. The people no longer ride in the spring wagon or lumber wagon. The story of good roads interests everybody. We now have a state highway commission, a state engineer and a lot of laws to fit the changed condition of affairs.

“Cowley county had two Walnut river bridges; they were what was known as the Newman mill bridge and later called the Country Club bridge, and the Ninth avenue bridge at Winfield. Both these bridges were old and dangerous, more especially the floor; to replace the floor would cost something like $1,000. This the county board did not wish to do so they decided to build two bridges. Billie Huston wanted a stone arch bridge of four 75-foot arches, a total of 300 feet clear water way. Billie knew that the Dunkard mill bridge, a stone arch of three 50-foot arches and one 40 foot, a total of 190 feet clear water way had for twenty years taken care of all the flood waters several miles down the river from Winfield, but he figured that the Ninth avenue bridge by reason of its location should be 110 feet more water way. It was a part of Billie’s plan to make the bridge higher and start the grade up Ninth avenue hill from the east side of the bridge. All stone bridges have an earth fill over the arches, therefore crossing the stream on a stone bridge the roadway is no different from any part of the road.

“I have told you what Billie wanted, as he told it to me and a lot of other fellows I could name. This story is written in memory of Billie Huston. He was a good friend of mine during all the sixteen years I knew him. Billie was a friend to everybody, good natured all the time, but with a great amount of stick-to-it-iveness in his make up. To illustrate this I must tell you about the part Billie played in the building of the new home at the poor farm. The old building was poorly arranged, there wasn’t a room in the building that could be entered without going upstairs or down. Billie’s heart was filled with pity and sorrow for the men and women who must end their days in the poor house and while they were objects of charity, not only Billie but all the county commissioners we ever had were inclined to be good to these old people. To build a new poor house [would] call for an election to vote bonds. This the county board feared would not carry, but the opportunity finally presented itself when the Peacock oil field was in full bloom. Lease money was in evidence and the county board was made some very good offers for a lease on the 140 acre poor farm.

“Grant Stafford was a bidder, and when Billie got him up to $6,000 for a five year oil lease, he went to the other members and told them that now was the time to do business. They thought so, too, and they traded a lease on the poor farm for Stafford’s check for $6,000. Billie’s joy was great; he could see a new home at the poor farm. He at once employed John Fuller to get up the plans. Bids were called for. I had the low bid and John Fuller’s fee for the plans just took the $6,000. If you will note closely the incident I am to tell, you will say, “Yes, that is Billie Huston.” The contract with me did not include any sanitary plumbing. Billie was afraid that the many might say that a majority of taxpayers had no bath tubs and other modern conveniences in their homes and people that went to the poor house had no reason to expect anything better than the fellows who furnished the money. Billie took another view of the matter. Nearly all the inmates were old and helpless and had to be waited on like babies and were a great task for the superintendent and his wife and these conveniences were as necessary as a place to sleep and eat. Anyhow, Billie contracted with the McGregor Hardware Co. to do this job for cost plus 10 per cent without consulting the other members of the board. When it was all finished Billie invited the board to go to the poor farm to see the new building, telling them what he had done, after it was done. Billie said, ‘I did not think you fellows would kick as one of my constituents, Mr. Grant Stafford furnished the money to build this fine home for the poor of this county, which includes those in your districts and it is only showing the proper appreciation to Mr. Stafford to put in these furnishings that are as necessary as the beds they sleep on.’ The claim was allowed.

“You may wonder what the building of the building at the poor farm has to do with the Ninth avenue bridge. Not very much, except I wished to show with what freedom our county board handled the business of the county. If you will follow me in my story, I am going to show you how little by little our affairs have been turned over to others and our county commissioners have been sewed up in a blanket with no authority to act upon their own judgment.Walter Sharp, “A Story About Bridges,” The Winfield Daily Courier, May 9, 1922.

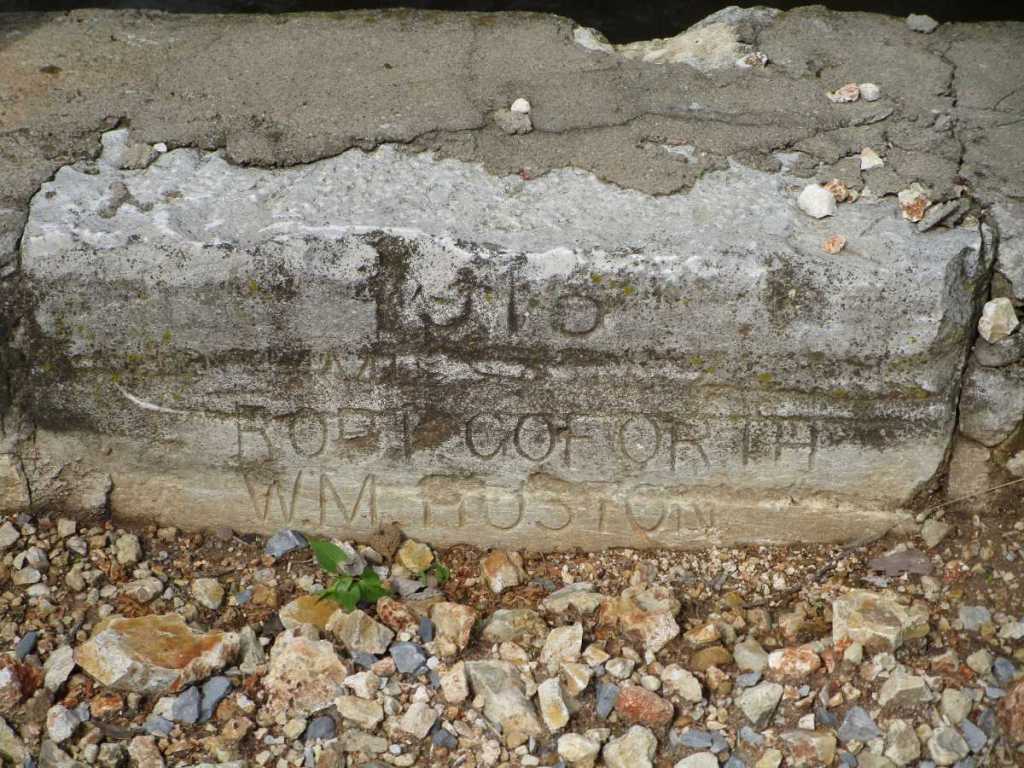

“Tom Clover says that Walter Sharp is Cowley county’s fourth county commissioner. Never was elected, never drew a dollar’s salary and has been continuously on the job for 30 years. That may or may not be so; anyhow I have in my story to the people of Cowley county gone to the bed rock for a foundation and am now to low water level. As the story progresses we will quarry the rock that makes the arch ring, dress it, hitch the derrick on it (which is the press), swing it to its place in the arch ring, then I will put in the key stone, then the county board will come out and see that the arch ring is grouted with a rich mixture, then we will build the wing walls and between the wing walls fill with that old fence Jones was glad to get out of the way and on top of that put [a coating] of river gravel. This bridge will then be completed and ready for acceptance.”

To see more of Walter Sharp’s story, click on one of the links below.