Long-spans are indeed possible in stone arch bridges, and have enamored builders for centuries, frequently resulting in local builders striving to outdo each other in being the builder of the longest span stone bridge in the area. While the average stone arch bridge span is quite modest in dimension (culverts are decidedly common), daring structures have been built of stone over the centuries. It seems that historically spans on the order of 200′, give or take, were commonly the limit for the really long-span stone arches; around 100′ was more common and did not require as much careful planning. One of the earliest stone arch bridges with a span over 200′ was built in the 1400s in Italy. This bridge had a span of about 250′, but was destroyed decades after completion. Its span was not exceeded for centuries. The key to building a long-span stone bridge is to understand what the limitations are that make a long span challenging to build. One such factor, of course, is the falsework for the arch; the bigger the span the more complicated the formwork becomes.

The Ultimate Limit

To design a long-span stone arch bridge it is helpful to understand what the limiting factors are. Ultimately, the limit to any arch is the point at which the self-weight exceeds the compressive strength of the material; even a line of thrust perfectly centered within the arch will not help if the material cannot handle the weight. That said, it is theoretically possible to build a stone arch bridge with an arch span in excess of 400 feet; considerably greater spans are also theoretically possible if high-strength stone (such as granite, for example) is sourced. If the stone is really good, spans well above 1000′ can be built. However, the problem with building spans of these lengths is that all the stone must be good quality, and the workmanship must be superb as well. Otherwise, crushing can occur, which will likely collapse the structure.

The Thrust Problem

Generally, the single most difficult problem of long-span stone arch bridge design is the thrust. Always a consideration, long spans are susceptible to the imbalance of the weight of the fill. Truly closed-spandrel stone bridges have a massive amount of dirt holding up the roadway to create a level driving surface. Since the arch is round and the dirt is added to create a fairly level surface, it follows that the top of the arch has relatively little weight while the haunches of the arch see a massive dead load. Normally, this is not a problem, but when the spans become large, especially if the arch is relatively thin, the whole may be entirely unstable, for the line of thrust tends to “escape” the arch out the top. This phenomena is more likely to be seen in segmental arches than, say, a Roman arch. As a Roman arch often has the opposite failure problem (the haunches tend to bulge out and the top of the arch tends to cave in) the imbalanced load on the arch works rather well towards stabilizing things. Unfortunately, most long-span arch bridges use segmental arches, as the high rise of a Roman arch may make a long span bridge utterly unable to be climbed, unless long ramps are added.

Open Spandrels

To relieve the bridge of this weight imbalance the spandrels are usually built open; in other words instead of a massive amount of fill added to the bridge, hollows are built between the arch and the roadway, relieving the weight imbalance as well as reducing the amount of material required considerably.

Open spandrels are most common in concrete bridges, but can be found in stone bridges as well.

Thicker Arches

A thicker arch can be used to help support a long-span bridge. As mentioned in our posts on arch theory, a thicker arch can be used to ensure the line of thrust remains within the arch; the extra thickness helps accommodate a line of thrust that does not track the curve of the arch. Unfortunately, a thick arch with closed spandrels is likely to be much more wasteful of material. This may not be a problem, though, as a thick, closed-spandrel stone arch bridge is much easier to build, allowing a saving in the skilled labor and design required.

An Interesting Historical Example

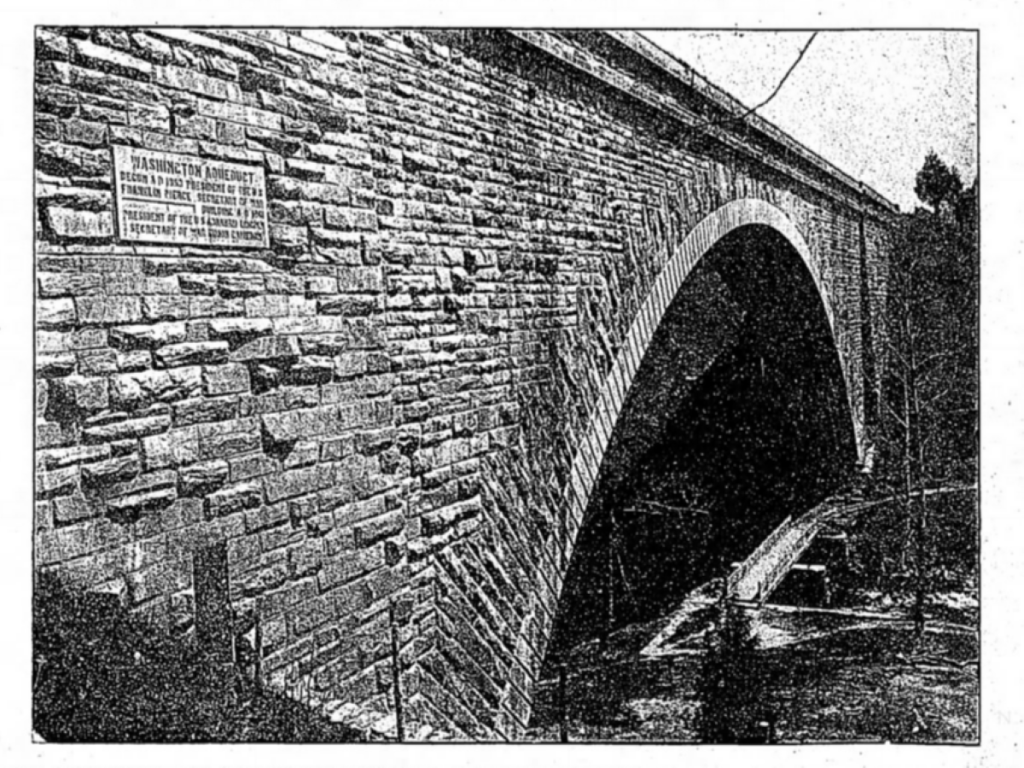

A historic example can be found of a record-breaking stone arch bridge that uses both a form of open spandrels and sections of extra-thick arch. The bridge in question is the 220′-span Cabin John Bridge near Washington, D.C., U.S.A., and was the longest span stone arch bridge in the world when built. This mid-1800s, record-breaking stone bridge looks like a closed-spandrel bridge, but is not. Hollows were built in between the spandrel walls, making the middle section of the bridge act like an open-spandrel bridge. Obviously, the spandrel walls, being solid, put considerable weight on the edges of the arch where they rest. To compensate, arches were built into the spandrels themselves. A close look at the bridge shows as subtle feature— above the ashlar granite arch, the spandrel walls contain a section of arch placed directly on top of the main arch.

Thus, though the spandrel walls are solid, the arch here is considerably thicker by virtue of the second arch ring placed above the main arch. The center of the bridge, with its built-in hollows, acts like an open-spandrel bridge and thus the arch here carries a relatively light load.

But For Closed-Spandrel Bridges?

In general, the average closed-spandrel stone arch bridge is best built with a shorter span. 100′ is certainly attainable if the arch is thick enough, and still presents a sizable span without, perhaps, the hassle of designing a record-breaking stone arch bridge span. The traditional closed-spandrel design is tried and true, but generally becomes impractical once the spans become very long. Of course, long spans can be bridged with multiple relatively short closed-spandrel arch spans; local conditions tend to dictate what is practical.